The recent events in India at the famed Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) have thrown up several questions.

First, what does the idea of ‘nationalism’ mean? Secondly, how should freedom of speech and expression be exercised in the modern day? And thirdly, how should the academia and society understand, respond and interact on these questions?

The fact that JNU is now at the forefront of such a debate in India clearly shows the central role of the academia in the life of a country.

While a lot of people only mention the ‘applied’ part of research, it is the theoretical work done behind the ivory towers of the world’s great universities which nurtures new ideas.

After all, little did anyone expect that the monograph written by one Karl Marx in 1848, over a period of about six weeks, would change the world, half a century later. In our own land, the power of the pamphlet written in 1933 by ‘some students’ at Cambridge, ridiculed by even Pakistan's founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah when it was written, became a reality fourteen years later — such is the power of ideas!

Despite being the result of a very creative process, Pakistan has always been wary of intellectual activity. Pakistan's history is rife with intellectuals being jailed, banned, banished, etc. Some quarters have erroneously given the impression that if these intellectuals are allowed to flourish, the state might disappear or God knows what catastrophe might befall on all of us. This, of course, was, and is, all nonsense.

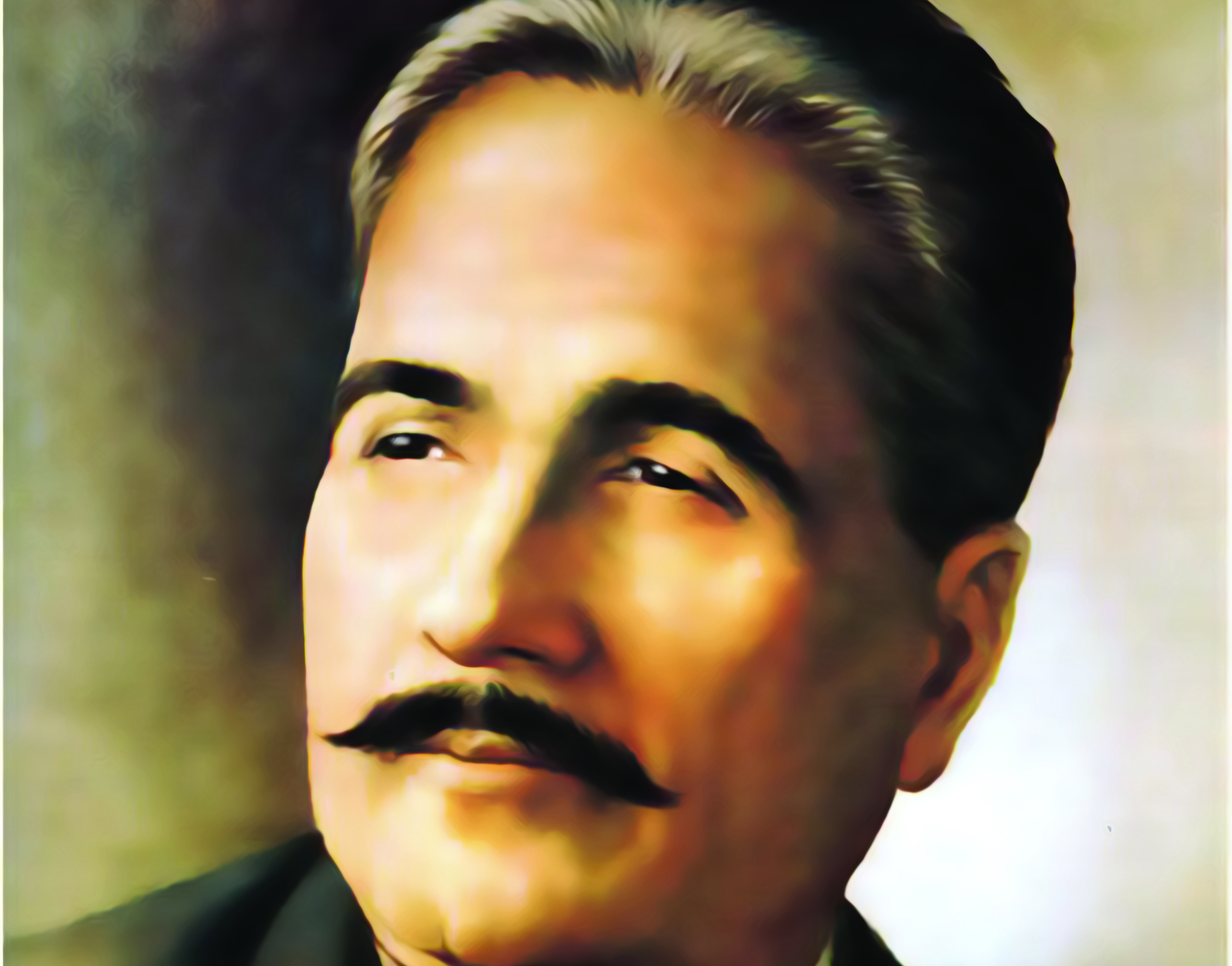

I often wonder how many people who revere Allama Iqbal as a poet and thinker have actually read him, and those who have read him — have they really understood him? This is because every single time I read Iqbal, I think he was one of the most modern and forward-looking thinkers in the world at that time and his vision was a dramatic reshaping of the world where the intellect would prosper. However, all of us in Pakistan want a holiday on his birthday, but rarely do we care to implement his vision for the Muslims of South Asia, let alone the people of the world!

The place where I work has a phrase from Iqbal’s poem, Takhliq (Creation) as its motto, where the full verse reads, in translation: “New worlds derive their pomp from thoughts quite fresh and new/From stones and bricks a world was neither built nor grew”. Here, in just one verse, Iqbal gives us the key for the creation of ‘new worlds’. So, if we really want to achieve that ‘good life’ as Aristotle put it, we must allow for the germination and promotion of new ideas and thoughts. We will never develop if we choke the intellectual process and stifle freethinking. Iqbal knew it and said it clearly, but we have yet to listen.

Since Friday, we have been holding the Afkar-e-Taza festival at the Alhamra in Gaddafi Stadium, Lahore. Inspired directly from Iqbal’s verse above, this event attempts to do exactly what Iqbal wanted — nurture and promote new thinking.

When Dr Umar Saif established the Information Technology University a couple of years ago, it was his firm belief that this vision of Iqbal must be realised, and this is our small intervention in this realm.

So for three days, we will hear from scholars from all over the world — Oxford, Chatham House, Chicago, Yale, Berkeley, Australian National University, Aligarh, Jawaharlal Nehru University, and several other places. We will hear from scholars of the calibre of Dr Faisal Devji, Dr Amin Saikal, Dr Maria Misra, Dr Peter Frankopan, Dr Catherine Asher, Dr Rajiva Wijesinha, Dr Steven Fish, Charles Allen, Dr Najaf Haider, and several others, and we will hear topics ranging from Mughal history, the French in South Asia, the Silk Roads, modern Afghanistan and Iran, and of course, Iqbal. - Express Tribune